Seeking a third opinion for metamorphopsia in his right eye, a 53-year-old sculptor presented to Michael Allingham, MD, PhD, Duke Eye Center of Cary retinal specialist, thinking a shard of stone had entered his eye during his work. A complete ophthalmic exam and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging showed normal findings with the exception of prominent drusen in the right eye, yet the patient’s symptoms of visual distortion were intensifying week by week.

“If all you see is drusen, your first thought is that this is dry age-related macular degeneration—it’s entirely possible for drusen alone, especially large ones, to distort the architecture of the retina, leading to these types of symptoms,” Allingham says.

While the OCT and exam were not consistent with a wet macular degeneration picture, as no subretinal or intraretinal fluid could be seen, there was still a disconnect between the patient’s symptoms and the examination and imaging findings. Despite the reassuring OCT findings, Allingham decided to pursue additional testing.

Question: What ancillary testing did Allingham use to confirm the presentation of wet macular degeneration?

Answer: Allingham used fluorescein angiography (FA) to identify a subfoveal occult pattern of leakage consistent with choroidal neovascularization (CNV)—the hallmark of wet macular degeneration.

“At Duke, we still believe very strongly that traditional fluorescein angiography has a role, especially in cases like this, as there are times when the fluorescein tells you something that the OCT does not,” Allingham says. “Going the extra mile in terms of testing doesn’t always change your management, but for a certain percentage of patients, it is really important.”

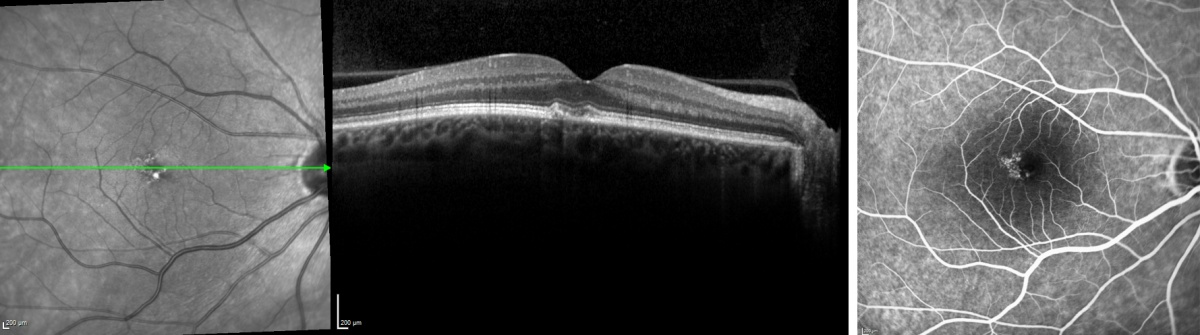

The pretreatment images below demonstrate the difference between the findings in OCT and FA. In Figure 1 (left), OCT shows subfoveal pigment epithelial detachment most consistent with drusen but with no subretinal or intraretinal fluid, and in Figure 1 (right), FA shows subtle but definitive late occult leakage affecting the fovea, suggesting active CNV.

Figure 1: Patient’s pretreatment OCT (left) and pretreatment FA (right).

Figure 1: Patient’s pretreatment OCT (left) and pretreatment FA (right).

For an eye with untreated wet macular degeneration, Allingham notes there is a 25% chance per year of developing a large hemorrhage under the retina that results in profound vision loss that is frequently irreversible. With this in mind, Allingham started the patient on an aggressive treatment plan to stabilize the CNV, performing an intravitreal injection to target vascular endothelial growth factor and prevent leakage, bleeding, and growth of abnormal blood vessels under macula. Four weeks after this treatment, the patient’s symptoms were completely resolved, and the occult leakage identified on fluorescein angiography had disappeared.

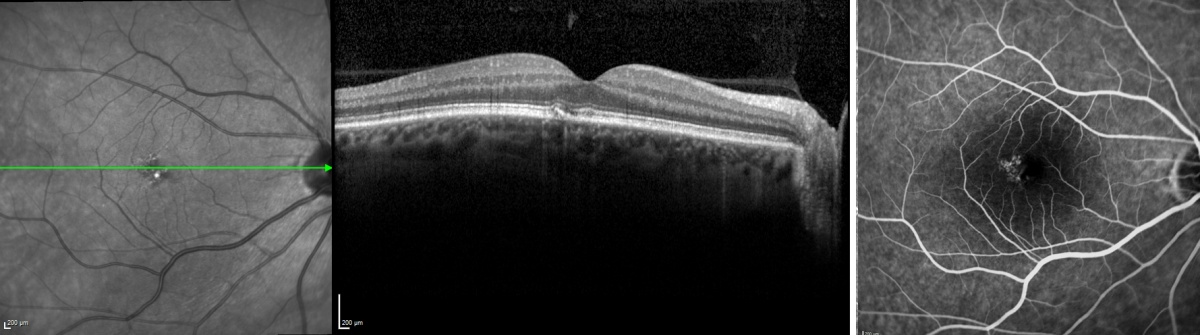

In Figure 2 (left), post-treatment OCT imaging remained unchanged, but in Figure 2 (right), post-treatment FA shows complete resolution of the leakage.

Figure 2: Patient’s post-treatment OCT (left) and post-treatment FA (right).

Figure 2: Patient’s post-treatment OCT (left) and post-treatment FA (right).

Due to Allingham’s early detection and quick action as well as monthly monitoring and treatment, the patient’s disease has not progressed in five years. He is able to maintain 20/20 vision with glasses, as the wet macular degeneration had only manifested in one eye, and he is able to continue pursuing his craft.

“The patient’s employment as a sculptor predisposed him to experience these symptoms in a more powerful way than others might have, and he is acutely aware of the fact that his livelihood depends on his vision,” Allingham notes. “This patient is a great example of how, if we can catch this disease at an early stage, we can preserve good vision and give people many more years of sight.”

Article originally appeared in Clinical Practice Today