Gene Therapy Aims to Help Eyes Produce their Own Medicine

New Macular Degeneration Treatments on the Horizon

Duke Eye Center is participating in two pivotal gene therapy clinical trials that may become promising treatments for age-related macular degeneration, the most common cause of vision loss and blindness in older Americans.

The studies, ATMOSPHERE and ASCENT are large multisite trials, and Duke is the lead site for the latter.

Both treatments involve a novel gene therapy that essentially turns the eye into a “biofactory” that produces its own medicine.

“This research is exciting because it could offer a one-time treatment approach,” says Lejla Vajzovic, MD, Associate Professor of Ophthalmology and Principal Investigator for the trials. “It may be a permanent fix for patients.”

In the treatment, a modified virus is injected into the eye. The virus contains engineered genes and cannot make people sick. Once in the eye, the virus spreads genes to other cells, where they produce a protein that slows or halts the disease process.

“We are introducing a novel gene that expresses medicine continuously in the eye,” Vajzovic says. “The results have been quite promising thus far.”

One-Time Treatment

The clinical trials are evaluating treatments for both kinds of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): dry and wet. In wet AMD, extra blood vessels form in the eye and leak, making the central field of vision cloudy or opaque and rapidly leading to severe vision loss. The dry form doesn’t always cause troublesome vision symptoms, but it can progress to the wet form.

Currently, there is no treatment for dry AMD, and the treatment for wet AMD requires regular eye injections, a burdensome regimen for patients. They must visit their eye doctor every month or two for the injections, and missed doses can lead to vision loss.

“It’s a lot to ask when life events happen, like surgery for something else, or travel, or a pandemic,” Vajzovic says. “Often these are patients who can’t drive, so now a family member has to come in and that adds another layer of complexity.”

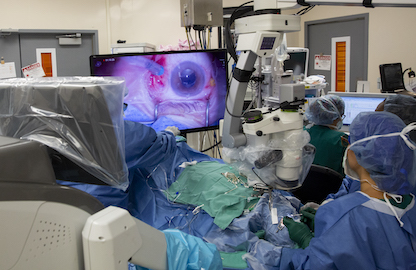

The new treatment being tested would replace all those visits with a one-time eye surgery in which a retina specialist would inject the modified virus underneath the retina.

Duke is participating in another clinical trial, called HORIZON, that is evaluating a similar treatment for the advanced form of dry AMD, in which clumps of cells in the retina die in a process called geographic atrophy. Patients with this kind of dry AMD can experience significant vision loss, although it progresses more slowly than wet AMD. In this case, the engineered virus injected during surgery contains genes that express a protein to tamp down the inflammation that drives geographic atrophy.

Ophthalmology at the Forefront

The eye provides an ideal site for gene therapy because it is a self-contained organ, which means drugs or genes injected into the eye rarely cause systemic side effects. It’s also a small organ, so doses can be small. Furthermore, imaging technologies give investigators an easy way of looking inside the eye to track the effects of the treatment.

For all these reasons, the field of ophthalmology is leading the charge when it comes to exploring treatments using gene therapy, with dozens of clinical trials underway.

In fact, the first FDA-approved gene therapy treatment in any medical subspecialty was for an eye disease. That treatment is for a rare inherited disease, but the treatments being tested as part of the ATMOSPHERE, ASCENT, and HORIZON trials have the potential to help many more patients, because about 11 million people in the United States have some form of AMD.

“Gene therapy is so novel and there are a lot of questions to be answered,” Vajzovic says, “but it’s exciting that ophthalmology is at the forefront of this approach, and it’s super exciting to be talking about having these options for patients.”