Access to technological advances, pediatric retinal expertise critical to restoring vision

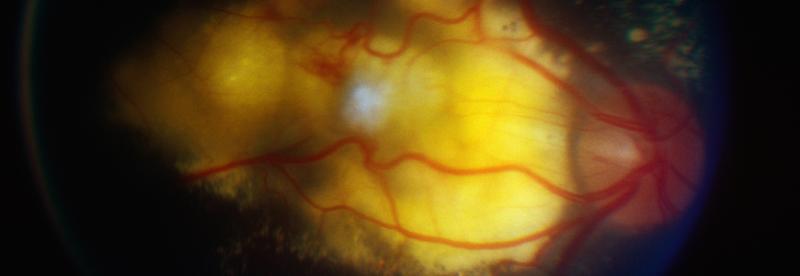

An 8-year-old boy presented to his local pediatrician with blurred vision and leukocoria, which indicated Coats’ disease, a rare, idiopathic exudative retinopathy found in children and adults. Even after several treatments with a local specialist to slow the growth of the retinal telangiectasia in the boy’s left eye, his condition gradually progressed to the start of unilateral exudative retinal detachment, consistent with stage 3 of the disease.

Concerned about further retinal leakage and swelling that could lead to a complete loss of vision or enucleation, the boy’s family traveled to Duke for a consultation with Lejla Vajzovic, MD, who is one of only about 50 pediatric retinal surgeons in the United States.

“Unfortunately, when a patient presents with Coats’ disease, it’s already typically later in the disease course, when the vision is blurred, we see the yellow reflex of the exudate, and the eye has begun to turn inward,” Vajzovic says.

Although the full pattern of this non-hereditary disease is unknown, Vajzovic says if it’s caught in time, some level of central vision can potentially be restored.

QUESTION: What methods did Vajzovic use to restore most of this patient’s vision?

ANSWER: Vajzovic used widefield fundus photography and dye tests to obtain advanced imaging of the patient’s left anterior chamber. She also performed multiple laser photocoagulation treatments to repeatedly treat the exudation and administered steroid injections to help decrease inflammation.

Widefield fundus photography pinpoints issues earlier in this disease presentation than other methods, she says: “This type of technology allows us to see the extent of the disease better and treat it earlier. Referring patients to centers that have this technology available to diagnose with fundus photography and dye tests is critical to saving their vision.”

An estimated 69% of cases of Coats’ disease are found in male patients, with the average age at diagnosis being 8 to 16 years, although the disease has been diagnosed in patients as young as 4 months old. The younger patients are when they present, the harder it is to examine them thoroughly in clinic, says Vajzovic, a leader of the Duke Pediatric Retina and Optic Nerve Center and a member of the Scientific Advisory Board for the Jack McGovern Coats’ Disease Foundation.

One benefit of this newer approach using widefield fundus photography is that patients do not require general anesthesia as often. In the past, patients would need to undergo anesthesia every few months so that the surgeon could perform a procedure or ensure there is no further disease progression. “This is important because the risks associated with undergoing general anesthesia tend to be higher than the procedure itself,” Vajzovic says.

Additionally, widefield fundus photography does not require dilation, making it especially helpful in pediatric cases. “It allows us to do a more thorough exam in clinic, but it doesn’t completely replace the need for anesthesia,” she adds.

Ultimately, early intervention with laser photocoagulation treatment and close monitoring of progression are needed in cases of Coats’ disease. “Depending on what state a patient presents in, we may have to do retinal detachment repair and subsequent cataract surgery. We typically hope to address it with just laser, though, which always involves multiple laser sessions.”

Despite the severity of diagnosis when he first presented, the boy did not require further surgeries after a number of laser photocoagulation treatments. With time, the retinal exudates subsided, and his vision was restored, though he lacks depth perception and has a slightly restricted visual field, Vajzovic notes.

“While he had a lot of yellowing in the macular region affecting his vision, he was fortunate that those went away,” she says. “He has done remarkably well in terms of his visual recovery.”

Article originally appeared in Duke Health Clinical Practice Today