Author: K. Lou Ward

The following is an expanded version of the original story published in VISION 2025.

Rami Gabriel, MD like many ophthalmologists who treat glaucoma, excels at administering eye drops. When his patients are particularly uncomfortable or post-operation, Gabriel tries to set them at ease. For his young pediatric patients, Gabriel encourages and “talks them up,” then quickly lifts the upper eyelid and plop. Quick and minimally invasive.

“But once they start squeezing, you’re at a loss,” says Gabriel.

Eye drops can be tricky for patients. After all, who isn’t a little wary the first time a doctor or technician holds your eye open, and you watch a mysterious droplet plumet through your vision and plop onto your eye? Gabriel remembers one young patient who had a especially difficult time. Not even in elementary school yet, this patient just received a glaucoma drainage device, or GDD, to help control increased eye pressure due to glaucoma, and they were squeezing their eyes shut with all their might. Gabriel knew how delicate the ocular tissue was post-surgery and how careful he needed to be. He started to recognize how difficult it must be for patients and their families to keep up with eye drops at home. This is a big problem because eye drops are critical to many glaucoma treatments.

That’s when an idea began to form. Gabriel, now a cornea fellow in Duke Ophthalmology, is devising an improved GDD to reduce or eliminate post operative eye drops, reduce surgery difficulty, and ultimately tackle the primary goal of treating glaucoma: preventing blindness.

Gabriel first came to Duke Eye Center as an ophthalmology resident with an interest in translational research, or research with concrete applications as products or services. Throughout his residency, Gabriel worked with many patients of all ages suffering from glaucoma, the second leading cause of blindness around the world and the number one cause of irreversible blindness.

“So once you lose it, you lose it forever,” Gabriel says of vision loss due to glaucoma. “We don't have any ways of growing back the nerves that glaucoma damages.”

With over 3 million Americans living with some form of glaucoma according to the CDC, this prevalent group of conditions is a special area of focus for many at Duke Ophthalmology. In glaucoma, fluid in the eye does not drain properly, which leads to increased pressure within the eye. Over time, this burgeoning ocular pressure damages the optic nerve and can cause deteriorating, irreversible vision loss and, eventually, blindness. There is currently no cure for glaucoma, but early detection and intervention can prevent further degenerative vision loss.

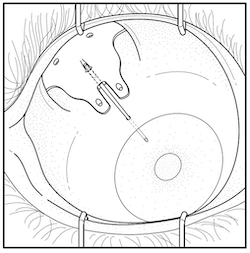

Typically, the initial glaucoma treatments are routine medicated eye drops or laser therapy, both of which aim to reduce pressure in the eye. But if these treatments fail to control ocular pressure, surgery is a patient’s last line of defense. There are different surgical approaches depending on the case. GDDs are one such approach. Once in the eye, this tube-like device diverts the accumulating fluid from glaucoma into a separate reservoir in the eye where the body can naturally reabsorb it. However, these patients often still need to use medicated eye drops after surgery to manage inflammation and prevent further vision loss.

For glaucoma patients, regularly applying eye drops can be difficult for a host of reasons, such as cost, regimen complexity, forgetfulness, lack of understanding, fear, or denial, as reported by glaucoma patients in one study. In clinical practice, Gabriel saw firsthand how burdensome the maintenance regimen of eye drops could be, especially for pediatric and elderly patients. But he also knew that patients needed the medication in the eye drops for their surgeries to work.

“You want to have a successful surgery every single time,” says Gabriel.

When medicated eye drops are too burdensome, surgeries can fail, and glaucoma can take a greater toll on a patient’s vision. But Gabriel has an elegant, yet simple, idea to help surgeries and patients succeed. For patients undergoing a last chance GDD implant, what if the implant itself released critical glaucoma medicine into the eye? Gabriel’s idea could at once relieve patients of ocular pressure and the pressure of applying eye drops post-surgery. Central to Gabriel’s concept is a hydrogel, a unique, dissolvable polymer loaded with the glaucoma drugs that slowly release into the eye over time.

Beyond reduced patient burden, Gabriel sought to improve glaucoma treatment for surgeons as well. As a resident, Gabriel’s job in the operating room was to prepare the tube component of the GDD as the chief ophthalmologist, glaucoma specialist, and mentor to Gabriel, Leon W. Herndon Jr, MD conducted the surgery. Herndon made the incision in the muscle of the eye and slipped the plate that would catch excess aqueous humor, the fluid built up from glaucoma, as Gabriel delicately tied off the tube at a separate station. In many practices, the primary surgeon performs Gabriel’s step after they implant the tube in the patient’s eye. This step requires finesse and can be cumbersome or lead to delays in surgery.

“Tying off all these tubes for the surgery,” Gabriel says, “I was like, ‘Well, maybe there’s a better way to do this. Maybe there’s a better way to do this for the patient too.’”

That’s why his improved GDD design eliminated the tricky step of tying off the tube. Gabriel soon found that the Duke Eye Center not only encouraged excellence in clinical practice, but it also emphasized mentorship, research, and innovation –– all features he credits as vital for finding a solution to a problem in glaucoma care.

When Duke clinicians like Gabriel identify an unmet need in clinical practice, they can tap into Duke’s broad research capabilities to find a way to make an impact. So, when Gabriel had an idea to improve GDDs, he had an entire network ready to help him turn his idea into an invention.

Gabriel connected with Herndon and Pratap Challa, MD, both of whom are professors of ophthalmology and experts in glaucoma. Challa studies the cellular and genetic foundations of multiple glaucoma conditions as well as applications in glaucoma treatment like drug delivery and therapeutics. Challa mentored Gabriel through the stages of translation research and is considered a co-inventor on Gabriel’s device.

“I've been very lucky to have some amazing mentors,” says Gabriel of Herndon and Challa. “Dr. Challa, who's my main mentor, has been teaching glaucoma for over 20 years, and it's one of the most prestigious programs to learn glaucoma from.”

While Gabriel and Challa iterated on the new and improved GDD, they also tapped into Duke’s innovation ecosystem resources and connected with Duke’s Office for Translation & Commercialization (OTC), Duke’s tech transfer office. OTC supports Duke researchers and inventors like Gabriel and Challa at Duke Eye Center and across the university to bring their innovative ideas to the market. The goal? To turn translational research into reality. Dennis Thomas, Ph.D., now retired associate director of licensing at OTC, worked closely with Gabriel to iterate his design, secure a patent, and devise a commercialization strategy –– the common path for turning translational academic research into fully realized products and services. Thomas and others at OTC regularly work with clinicians from Duke Eye Center and Duke Health, like Gabriel, with the common goal of getting technologies to the clinic.

“At OTC, we have a lot of the tools that people need for translational research and moving it out into the into the public,” says Thomas of the Office’s expertise and resources in patenting, spinning out startups, and connections to research funding.

Since Gabriel started working with OTC in April 2023, he and Challa have received a US Patent Application for the hydrogel GDD device. Thomas is also connecting them with potential industry partners, pharmaceutical and medical device companies that want to take the invention to the next step. Players in Duke’s innovation space like OTC are experts in bringing academic ideas to the market, and they bring expertise in navigating the circuitous path of research translation, according to Thomas.

For Gabriel and Thomas, patient outcomes are the north star of their commercialization and patenting strategy. Rather than designing a brand-new device, they’re approaching this as an improvement to existing treatment that is made up of constituent parts already approved for safe use by the FDA.

“I think by making it more of like a device upgrade, instead of a whole new device,” says Gabriel, “we can decrease the regulatory period, and that way patients can get it sooner.”

With the support of his mentors and Duke’s innovation infrastructure, Gabriel was able to devise a new device that eliminates a key barrier for patients –– eye drop burden –– and improves surgeries for practitioners. And like many innovative clinicians at Duke Eye Center, Gabriel’s inspiration was borne out of caring for his patients. As he continues to work with OTC on his drug-eluting GDD, he and his fellow clinicians at the Duke Eye Center continue to pursue novel translational ideas that can improve clinical practice at Duke and patient care everywhere. And as more funding organizations see the potential in young innovators like Gabriel or seasoned inventors like Challa, their impact on patients promises to grow.